Momiage pine pruning at Niwaki HQ

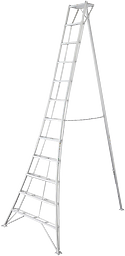

Following on from our inspiring visit to Great Dixter for Niwaki Field Report No.1, it was our pleasure to return the favour and welcome Rob, Talitha, Matt and Luke to Niwaki HQ for a winter pine pruning workshop with Jake Hobson. Read on for the lowdown from high up a Tripod Ladder.

The Japanese name for winter pine pruning is ‘momiage’ (Moh-mee-aggeh) which literally translates as ‘sideburns’…but don’t let that confuse you: essentially, momiage is the practice of stripping last year’s needles from the tree, leaving 7 or 8 pairs of fresh, green needles only.

Of course, like all codified activities, different gardeners in different regions of Japan have different rules. Kyoto gardeners, for example, recommend leaving 15 pairs of needles: perhaps because their winters are harsher and their summers are hotter (compared with Tokyo) there is reluctance to stress the tree more than necessary. Or maybe it’s an aesthetic choice, or, very likely, a combination of aesthetics and practicalities.

Momiage also involves thinning buds, which is where Niwaki Snips come in handy: aim to thin out excess buds as you pluck needles, removing the central bud to leave a pair either side, or sometimes leaving only one bud depending on neighbouring branches’ spacing. So much depends on the summer’s growth and how hard you pruned the tree during ‘midoritsumi’ (the corresponding early summer trim – a story for another day), as well as the species of pine you’re working on. There’s whole books on this stuff…see ‘Niwaki’ by Jake Hobson, for example (link below).

Why do it at all, you may wonder? While it’s true that pine trees do survive quite well without this level of intervention, removing the dead pine needles isn’t purely for aesthetic reasons: the tree benefits from the extra light reaching the healthiest needles, especially in areas lower down the tree which would otherwise languish in the shade. Pine needles are nothing but modified leaves, of course, meaning year-round photosynthesis is their main task. The combination of weak winter sun and the reduced surface area of their spiky design means they can always use a helping hand.

Some people like to imagine the tree having three zones (top, middle, bottom), and they aim for a slightly thinner top section, allowing more light to filter through to the lower levels.

It’s a tactile, meditative process conducted largely without tools. Begin at the top and work down the tree, stripping the dead needles by hand as you go. Along the way you might decide that you want to remove a rubbing branch or else clarify the shape you’re working towards by removing the odd undesirable offshoot here and there, so you would be well advised to keep a pair of secateurs and a pruning saw with you as you climb the ladder: that way you can act on impulse.

Not that it’s a bad idea to view the tree from ground level before you make any major trims, especially if you’re still learning the ropes. Often, the overall shape can appear very different from standing height compared with up close on a ladder. Some Japanese gardeners maintain that each tree has its own ‘keshiki’ – that is ‘landscape’ – which you’re aiming to reveal as much as to invent, and this is best considered by viewing the tree as a whole.

Jake gave a brief presentation to explain the general concept, show the difference that annual pine pruning and shaping can make and discuss ‘ideal’ forms: zig-zagging patterns forming asymmetrical shapes, with an emphasis on exaggerating the peculiarities of pine growth patterns and the essential elements of the tree.

Following a practical demonstration at ground level, it was time to select a tree and ascend the ladders to get to work. As everyone’s confidence grew, the questions and chatter died down, leaving the team to ponder and pluck in peace. It’s slow work that is often conducted with several gardeners per tree. In temple gardens you might see as many as 5 or 6 gardeners working on a single tree at a time – testament not just to the number of people employed in the gardening industry in Japan but also to the importance attached to these trees*.

It’s sticky, messy work. The fragrant sap is almost impossible to remove from clothing, which is where Arm Covers come into their own. Scruffy clothes are probably a good idea too, just in case.

We asked Jake how, if at all, momiage is applicable to gardening in general. He replied “the attitude that thinning foliage is desirable for aesthetic and plant health reasons is one to consider, as is the idea that revealing a tree’s branch structure can be pleasing. Any old conifers would benefit from shaking and removing old brown needles, and that first step can easily move on to a light thinning, which in turn can pique the interest and encourage further steps, and before you know it you’re in full momiage mode!" So get out there and take a second look at those overlooked conifers.

When it’s all done either leave the discarded needles to mulch into the ground or use an adjustable-width rake to tidy up, then take a step back to admire your handiwork (and spot the bit you missed!).

* Keep your eyes peeled for the Niwaki Field Report No.2, planned for late summer 2025, with a special feature on just one such temple garden team. Meanwhile you can read our article on Great Dixter in Niwaki Field Report No.1 (available now!).